Ever since a paleontologist discovered the first Homo neanderthalensis skeleton in 1829, scientists have tried to piece together why Homo sapiens eventually thrived, while Neanderthals disappeared around 40,000 years ago.

By comparing their prehistoric skulls to ours, scientists learned that Neanderthal brains were slightly larger than ours, both at birth and at full size, and that they may have lived longer than our ancestors. So why didn’t this evolutionary advantage help Neanderthals dominate humanity?

Using biomedical computer imaging software and Neanderthal skull fossils, three Japanese researchers have now mapped out how specific portions of Neanderthal brains compared to ancient humans—and how specialized portions of Homo sapiens’ brains may have contributed to their survival over Neanderthals.

Published in Scientific Reports (SR) earlier this month, “Reconstructing the Neanderthal brain using computational anatomy” revealed that our ancestors’ cerebellums were significantly larger than ancient Neanderthals’.

And the researchers theorize that humans’ larger cerebellums gave them “higher cognitive and social functions including executive functions, language processing and episodic and working memory capacity.”

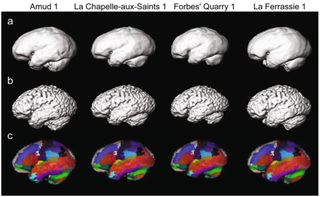

The researchers combined Neanderthal brain models (a) with modern human scans (b) to label theoretical parts of the Neanderthal brain (c) | Credit: Kochiyama et al.

Because of their allegedly inferior communication skills and long-term memory, Neanderthals may have had more trouble adapting to climate change events like ice ages than Homo sapiens.

To reach this conclusion, the researchers scanned 1,185 healthy human brains, then compared them to the fossilized skulls of four ancient Homo sapiens and four Neanderthals. They then created 3D virtual “casts” of the skulls, and compared them to modern brain scans to map out how they might have looked when still alive.

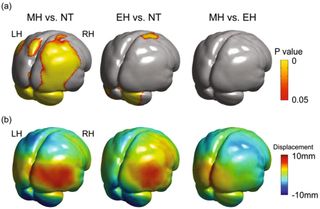

The shape displacement between early humans and Neanderthals showed how our brains mostly differed on the right side, where the cerebellum rests | Credit Kochiyama et al.

A previous 2013 study theorized that Neanderthals’ brains devoted more cognitive power to better vision and motor control, and suggested that higher thinking could have been impaired as a result.

But as SR co-author Naomichi Ogihara told Scientific American, they are the first to actually digitally reconstruct Neanderthal brains.

“Our method allows estimation of the shape and volume of each brain region, which is quite impossible just by analyzing the endocranial surfaces.”

Once inside these prehistoric brains, Ogihara and his colleagues were surprised by their findings. “We initially expected that the frontal lobe would be different between the two species because it has been considered to be related to higher cognitive functions, but it was not the case.”

Instead, while our frontal lobes looked mostly the same, our cerebellums had significantly more cognitive power. This region helps coordinate cognitive processes in different parts of the brain in the correct order, and our larger cerebellums increased our processing capacity.

Basically, we lucked into a better CPU, and Neanderthals just couldn’t keep up.

Robin Dunbar, an evolutionary psychologist who spoke to Scientific American about the research, emphasized that this research doesn’t prove that Neanderthals were “any less human, or shambling ape-men”. Instead, the difference would have been subtle; but as Ogihara said, subtle differences “may become significant in terms of natural selection.”

One theory among many

While this research makes a compelling case, other scientists have jumped in to point out some flaws in the analysis.

We know that Neanderthals went extinct, but it’s still unclear if their tiny cerebellum was a primary factor, compared to many other potential causes for extinction.

Lana Ruck, a cognitive science doctoral student at Indiana University, told Gizmodo that healthy humans tend to have varying sizes in cerebellums, and that this deviation doesn’t necessarily correspond to lower executive functions or memory in contemporary humans.

And Washington University neuroscientist Kari L. Allen claimed that, while the SR study “rel[ies] on the premise that bigger is better and that shape of the brain surface can be used to interpret the size of brain components,” mainstream neuroscience may not back up their beliefs.

In fact, Allen says, “the overall shape of brain is almost certainly a compromise of multiple factors and some of these are likely to have little impact on cognition.”

So, while this study could lead to an influx of research on digital recreations of ancient human brains, it’s still unclear how much this research will actually be able to tell us.

Comments

Post a Comment